THE FACT IS

(Originally posted on the website Continuum…)

THE FACT IS, my father has cancer.

It was not the shock that came first. It was the dullness, like the feeling you get after a bully punches you in the stomach. First, you cannot breathe. Then you get dizzy. Then the actual pain, the shock, from his fist connecting with your abdomen is realized.

I tell people about it. The clinical details leave my mouth. My ears hear my own voice, but they do not believe I am talking about my own father. It cannot be. Surely, it is another man’s pancreas being talked about. Certainly, it has already spread to another man’s liver. Someone please tell me that the details are about another person’s father because I cannot believe my own words.

The fact is, it is true. My father has cancer. It is already at stage four. It is already spread to his liver. It is inoperable. Chemotherapy cannot beat its aggressiveness. Neither can my denial make it go away.

My father came to see our new house in the beginning of February. He was in a great mood, probably happy that I had my own place again. We talked for a while as he flipped through one of my MAD Magazine on the coffee table. My drum set impressed him. However, my seldom used Fender 12-string acoustic guitar caught his attention. “When are you going to teach me to play?” He said he had been desirous of learning to play the guitar.

During that visit, my dad told me that he was having pains in his stomach for a few weeks. It had gotten to the point that he was fairly uncomfortable. He was scheduled for an ultrasound a few days after that.

A week went by before the results came back. Yes, there was some type of mass on his pancreas. A biopsy was to be done next.

After the biopsy, another week went by. Then, the evening before my birthday, I received the call from my stepmother that my father had cancer. It was confirmed that he had what we all feared, what we all prayed he would not have, what we all could not believe.

My father is only 65 years old. Other than continuous, mild back trouble after falling from an electrical pole in his days as a lineman, he has been generally healthy. A few years ago, his physician detected a minor sugar problem. Still, he has maintained an active life since retiring at the age of 55.

How then is it possible to go to the doctor because of pains in your stomach, only to be told that you will die in two months if you do not start some type of treatment immediately? How do you move from a casual visit with your son to your first appointment for chemotherapy at a hospital in just a few weeks? How do you slip from the false comfort of presumptuous immortality to the stark realization of your inherit mortality in the amount of time that it takes your doctor to pronounce your diagnosis?

A few days after his diagnosis, my kids and I went to see my father. We bought an acoustic guitar for him, complete with a digital tuner and a nice leather case. Though he was surprised and happy to receive our gift, he still gave me the “son, you shouldn’t have spent all that money” lecture. I told him not to worry about it because it only cost a few million dollars and, “Heck, Dad, I make that in two hours of work!” The money was inconsequential. We only wanted him to know how much he meant to us. We regretted not doing more thoughtful things for him years ago.

The by-product of a terminal disease’s discovery is regret. As soon as you begin to realize that a person is not going to live forever and ever, the “should’ves,” “would’ves,” and “could’ves” start piling up in your mind.

“I should’ve picked up the phone and called him just to say hello.”

“I would’ve gone fishing with him every weekend if I knew he would one day be gone.”

“I could’ve told him I loved him more often.”

We assume that the people in our lives will always be there. Death is too frightful to keep in our minds. It is dark, scary, unknowable, and final. It seems easier to cope with life by having a mindset that assumes that the people we love will always be in our lives. We think of them as constants. They are reference points that delineate the boundaries of our lives. Another online writer expressed the same thought when her father passed away not too long ago:

“We all knew it was going to happen. It was both expected and unexpected, expected because of the bad health and unexpected because goddammit, there are certain constants in your life, and your parents are supposed to be one of them.”

Though it may be easier to cope with life for a time by conning ourselves into believing that the people around us are immortal, in the end, the fact of death has to be faced. As it turns out, our self-deception in the matter is the seedbed of many regrets. As long as we continue to think that there is always tomorrow to make the effort to communicate our love to someone else, we continue to sow seeds of regret. The more we procrastinate, the more our regrets will grow and spawn. It is inevitable. The fact is that death comes, sooner or later.

The fact is that we need to love and care about those around us in concrete and substantial ways now. Tomorrow is promised to no one. It may not be the easiest thing to do. It may require forgiving someone. It may require asking for forgiveness. It will require our best effort. To neglect to do so will seem easier for the moment. But the day will come when that neglect will require a more sorrowful effort in the end.

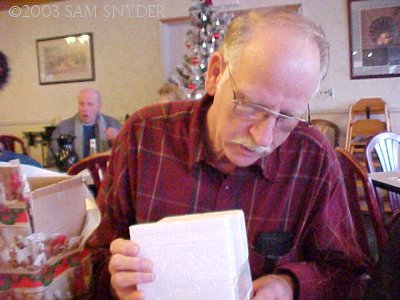

I saw my father this past Sunday. He had had his second chemotherapy treatment two days before that. One of the constants in my life began to tremble as he opened the door and then tottered a little due to his weakened condition.

“You see what I was talking about, son?”

Yes, Dad. I see.